| 17th September 2006 01:57 PM |

|

|

| Gazza |

Generation terrorists

It seemed like it was all over for the Who, one of rock's defining acts. But with their first studio album for 25 years, and a series of blistering live shows, Pete Townshend and Roger Daltrey are back and as vital as ever. From Live8, the internet and Pete Doherty to the dramas and tragedies that they've survived and their own explosive relationship - the Sixties icons talk candidly to Simon Garfield about what drives them forward

Sunday September 17, 2006

The Observer

About three years ago, Pete Townshend and Roger Daltrey had a conversation that went something like this.

Daltrey: 'Whatever you do, Pete, I'll support you!'

Townshend: 'Great, because I've got this idea that I want to do this musical in Las Vegas called The Boy Who Heard Music.'

Daltrey: 'Where?'

Townshend: 'Las Vegas.'

Daltrey: 'I'm not going there.'

Townshend: 'But you said you would support me in whatever I want to do.'

Daltrey: 'Except Las Vegas.'

Townshend: 'But it's only in Las Vegas that we'd get the 200 million dollars that I'd need to make my exploding Mirror Door moment.'

Daltrey: 'Yes, but whatever else you want to do, I will completely support you.'

A short while later, Townshend gave him some early chapters of his novella about three kids in a band.

Townshend: 'Well, could you read the story, because I want to write some songs about it?'

Daltrey (after reading it): 'It's the same old shit, isn't it? Come up with something new!'

Townshend: 'But this is it. This is me. I only have one story, one thesis. I'm a cracked record, and it's going to go round and round and round until I die.'

Such, at least, is Townshend's recollection of the conversation. He had endured these sorts of dispiriting exchanges with Daltrey before, and decided to press on regardless. One of the first songs he wrote was called 'In the Ether', which, like many of his compositions, appears to be about spiritual awakening and the expiation of pain. Townshend considers it, without question, one of the best things he has ever done, proclaiming, 'I am writing better Stephen Sondheim songs than even Stephen Sondheim is writing!' Initially, Daltrey was less convinced. 'I played it to Roger,' Townshend recalls, 'and about a month passed. In the end, I got on the phone and said, "So, what did you think?"'

Daltrey: 'It's a bit music-theatre. Maybe if you didn't have piano but just had guitar ...'

Townshend: 'Yeah, and maybe if it was three guitars and was rock'n'roll and sounded like "Young Man Blues" it would be OK.' And then Townshend put the phone down. 'I was really, really hurt,' he says.

But three years later, and 25 years since the last one, we have a new studio album by the Who. Endless Wire contains 19 tracks, 10 of them comprising what Townshend calls a 'full-length mini-opera' entitled Wire & Glass. Its creator is 61. He looks his age as he walks into his recording studio in Richmond at the end of August with the latest mix of the CD in a bag over his shoulder, but he looks good with it, not excessively ravaged, grey in a dignified way. He puts the CD into the mixing desk, and Daltrey's voice fills the air: 'Are we breathing out/ Or breathing in/ Are we leaving life/ Or moving in/ Exploding out/ Imploding in/ Ingrained in good/ Or stained in sin.' It sounds like they've never been away.

'In the Ether' soon follows, as do several love songs, several songs of yearning, and several very angry songs.

The angriest is called 'A Man in a Purple Dress', an attack on the trappings of organised religion written after watching Mel Gibson's The Passion of the Christ. 'It is the idea that men need to dress up in order to represent God that appals me,' Townshend explains. 'If I wanted to be as insane as to attempt to represent God, I'd just go ahead and do it; I wouldn't dress up like a drag queen.'

The song 'Mirror Door' imagines a place where legendary musicians gather after their death to drink and discuss the value of their work. Elvis and Buddy Holly are mentioned, alongside Howling Wolf and Doris Day. It was only after the recording was finished that someone mentioned to Townshend that Doris Day was still alive. 'I was absolutely convinced she was dead,' he admits. 'But I went to the internet and there she was - a fucking happening website!'

When the album is over, Townshend offers me tea in an upstairs room overlooking pleasure boats and rowers on the Thames. It is time for something he does better than almost any rock star of any age - the analysis of his craft, the opening of a vein in the process of confession. It is hard to imagine that anyone has thought deeper about their role in popular music, or produced such honest appraisals of triumphs and failures. It is no surprise that Townshend's most enduring work - Tommy and Quadrophenia - arrived in the form of a concept. From his art-school education and finely crafted emergence as a mod, right through to his new mini-opera, the music has never quite been enough without a story, and the stories aim to be both universally appealing and intricately personal. Sometimes they hit and sometimes they don't, but precisely why this should be is something that Townshend is still struggling to comprehend. As Roger Daltrey told me a few days later: 'He always needs a bigger vision, but some of his narratives are just so difficult to understand. He's talking about the ethereal and the spiritual, and it's very difficult to write that stuff down.'

Townshend's personal story is equally complex, and frequently auto-destructive. When he used to smash guitars on stage it was only part-publicity stunt; he really was raging against something he couldn't explain. These days, after years of therapy and creative output, he has found a more eloquent expression for his joys and torments.

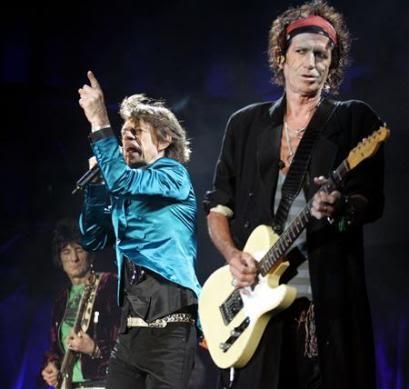

'The dream that is at the heart of the Who's work is a dream that I think Roger and I have realised,' he says. 'That dream is ... It's like the Stones at Twickenham. They're a pub band, but they're up there in front of many thousands of people, and what happens is quite extraordinary. Even though I understand they didn't play their best ever concert at Twickenham, a bunch of people I know who were there say, "It didn't matter. What matters is that we were there together." As artists, we can affect gatherings of people. People lose themselves, and in the moment of losing themselves they then find themselves. They find a commonality, an innocence, and a sense of being which, I suppose, is close to a meditative state. When they walk away from it, they look back and think something special happened.'

Townshend refers to his current band as Who2, not so much to separate it from the band that existed before drummer Keith Moon died in 1978 and bassist John Entwistle died in 2002, but more to reflect a state of mind. Townshend, and probably Daltrey as well, have come to recognise that rock bands have a certain natural life, and their survival beyond that depends on an acceptance that its most creative and famous days may be over, and should be celebrated. I mentioned that the Who I saw play a couple of years ago at the Forum and Royal Albert Hall - in which the mesmerising power of Daltrey's singing and Townshend's playing seemed unprecedented for a couple of guys approaching their sixties - reflected a remarkable rejuvenation of spirit, but he questioned my interpretation.

'It's not a rejuvenation at all, because we really don't have that in us. I think it is a rebranding, a recognition that the old Who brand is inviolable. It's just inviolable. There's almost nothing you can do with it. This was my problem in the Eighties - the brand was just so powerful. Who fans didn't like the last couple of albums that we made, It's Hard and Face Dances - and they weren't made lightly, they were struggled over - but they just didn't fit the model of the brand. So I sensed that what Roger and I should do was honour the brand, honour the history, honour the classicism. We should respect the fact of what we did, and accept our knighthood. And just live with it. And then the knighthood ties us to charity work. Anything that we do now has to be seen in context of that, but we can also draw a line and make a new start.'

The Who have just embarked on the second leg of a world tour. The live band has expanded to a six-piece - Townshend's brother Simon on second guitar, Pino Palladino on bass, John 'Rabbit' Bundrick on keyboards and Zak Starkey on drums - and nothing has pleased Townshend more than the reaction to recent shows from younger musicians. The Fratellis and Oasis enthused backstage, but approval from Paul Weller meant the most. 'If that cynical guy thinks it's OK ...' Townshend reasons. 'He was always very stern with me. You know, "Don't go back, don't ever go back, you're going back, I would never go back ..." I would just say, "Listen, I don't know if I could ever do what I did again." I sit and look at "My Generation" and "Won't Get Fooled Again" and I think, "How can I do that again?"'

You mean, you felt you can never better that?

'Yes, it was intuitive. And being intuitive is fucking difficult.'

I wondered how it was possible that the Who today looks less old than it did 20 years ago. 'Yes, something has happened,' Townshend says. 'People don't mind if you're old, as long as you're content. What's unbearable is somebody who's old and won't let the past go.'

I had first met Townshend in 1985, not long after he had begun working at the publishers Faber & Faber. He helped me with a book I was writing about exploitation in the music industry. The Who had signed some disastrous early deals, and Townshend told me one reason for this: 'Every major contract that I've signed, I think, has been done in a dressing room, or I've signed it when I was drunk ... Can you imagine actually trying to sit down in the middle of a tour and explain a very complex bit of tax law to somebody as stoned as Keith and I used to be most of the time, or as thick as Roger used to make himself out to be?'

He says he went to work at Faber because he 'needed some dignity'. He liked the idea of regular employment without pressure to deliver solo albums to a shrugging audience, and he offered a creative service to writers and photographers who wanted to tell their stories. His job coincided with the longest fallow period of the Who, from 1982-89, a period in which Townshend told everyone the group was no longer relevant. 'There were two real reasons I stopped the band when I did,' he says. 'One was that I blamed the rock industry for the death of Keith, of Brian Jones, of Jimi, for the death of 11 kids at Cincinnati at one of our shows. I felt that we hadn't looked after our own, and there was something wrong with our business.

'But I also felt we'd worn out the form. Punk had shaken everything, but what followed was computers and Linn drums and Heaven 17 and Scritti Politti. Interesting music, but quite manufactured and complex, and much less of the blood. I felt that my role in that world was over. And I would get these regular visits from Roger saying, "I want to do this, I want to do that," and I would say, "Listen, it's over. Fuck off." Well, I wouldn't say fuck off, but "I'm not your man". Watching him pretending to be who he was ... it was all just pathetic. I had very little sympathy for him. I thought he should really go back and be a builder. A woman said to me the other day, "But he couldn't let it go." I said, "Well, why not?" "Because he was fucking gorgeous!" I said, "Is that really what it's all about?" and she said, "There aren't very many gorgeous men in the world."

'Looking back now,' he adds, 'it does seem very cold of me to have brought down such a heavy door. John Entwistle was very resentful as well. What happened with John was that he'd got used to living high, and his money supply was cut off. In the end, when Roger came to me and said, "Listen we've got to help John, let's try to train him to live less high," and we couldn't do that. And as we trained him to live less high, he died. He didn't want to live less high. He preferred to be dead, in a sense.'

He thinks of another reason he broke up the band. 'I didn't want to be in fucking pain all the time. I didn't want to be so disdainful or so intellectual or so arrogant. I didn't want to be doing interviews with people saying [moany voice] "What's it like being old, and you said you wanted to die before you got old." I remember thinking, "Are these people vegetables or something?" '

Did drugs have much to do with the break-up?

'No. I drifted into drugs immediately after Keith's death in 1978. By 1981, I was fairly full-blown. It's certainly not a period I regret - I had quite a wonderful time. The only thing I regret is that the dabbling with drugs meant that I stopped drinking. I was a very, very functional drinker. I used to love alcohol. I didn't love being drunk, but I loved drinking. Drifting into cocaine, because everyone else in the world was doing it except me, and then finding that all that really did was increase the amount that I drank - I think that did create what toppled me physically. My real descent into extreme narcotics like heroin was a bit like that Pete Doherty thing that he's elongated into a life story now. I was trying to stop drinking, thinking, "Well, if I stop drinking I can use this, and if I use this then I can use that, and that's prescribed, and that's not prescribed ..." and in the end you're thinking, "I can't deal with this - please help."'

What are you thinking when you see Pete Doherty self-destruct?

'He's such an intelligent man. I completely understand, I just understand.'

In the past few years, Townshend has been writing his autobiography, but it is a slow process. In effect he has been working on it since the mid-Sixties, dutifully keeping old receipts and correspondence and many photographs in the hope that they would one day become revealing. And so they are. Townshend mentions one photo in particular by his friend Colin Jones, an iconic image of the Who posed in front of a Union flag at the time of 'My Generation'. Townshend is in the front in a Union Jack blazer. 'With this fish-eye lens, it made my already quite prominent nose look massive. You can see if you look at it that I'm crying, because Chris Stamp [the band's co-manager] and Colin Jones were making me ugly rather than beautiful, and taking my worst feature, which I now regard as my best feature, and exaggerating it.'

The book, which Townshend is writing chronologically, has now reached 1970, and he has shown early drafts to Stephen Page, the chief executive of Faber, and Jann Wenner at Rolling Stone. It is called Pete Townshend: Who He. He says he is blessed with a good memory, but he found a peculiar gap. 'I went to my mum and said, "Weirdly enough, I can remember from 13 months up to four-and-a-half, but then from four-and-a half to six-and-a-half, I can't remember anything."'

His mother, now in her mid-eighties, said there was a reason for this. Townshend was born in May 1945, a few days after VE Day. His mother was keen to celebrate victory by singing with his father, a saxophonist in the RAF dance band the Squadronaires, and she would follow him around the world. 'So my early years were a mixture of unbelievable glamour and unbelievable shock at being dumped with my grandmother,' Townshend says. His grandmother lived in Westgate, on the Kent coast. 'She turned out to be clinically insane and very abusive, and sexually abusive, or possibly something going on around her that was sexually abusive - this loon grandmother who walked around naked under her fur coat and tried to shag bus conductors.'

His mother's recent revelations filled in the years Townshend had blanked out. 'As she was telling me, I fell in love with my mum again, because she came out of it looking terrible, but she had the courage [to tell me]. And though it was shocking, it was the making of me as an artist.'

For as long as he can remember, Townshend has been intrigued by the components that make rock music both so effective and so destructive, and he has made compelling connections.

'It's because of this denial that anything ever happened to us during the war. We're worse than the Germans, worse than the fascists. There's all this echoing damage going on. I began talking to people, and found that, almost universally, people who had been evacuated had been unbelievably traumatised. But they had been refused the option of any mention of the trauma. Because what had actually happened was victory, peace, 'you're lucky'. I believe that when rock'n'roll came along, it had to happen. It sounds pretentious, and I never set out do it, but Tommy was an allegory of the postwar British condition.'

In January 2003, Townshend became suddenly aware that his life had taken a dramatic new turn: he recognised himself in a newspaper report as the 'famous rock star' the police were about to question as part of an investigation into child pornography.

'There were two things that went through my mind,' he says. 'One was that I don't deserve to be on the front of any tabloid newspaper. And two, this is gross hypocrisy that I'm obviously going to be sacrificed. So for a moment I thought there's just no point trying to continue. Luckily, Rachel [the musician Rachel Fuller, his partner since 1998] was next to me when I read the paper. I turned to her and said, "Fuck, this is the end," and she said "No, it isn't. Let's go and make a few phone calls ..."

'After a while I did actually realise that it wasn't going to have the sort of massive effect that I feared. But my first fear was that I was going to be framed. On the basis of the evidence and my immediate admission - I coughed up straightaway that I had used a credit card to access a website, as part of research - it would be then assumed, "Ah, we've got your number," and they would then feel inclined to frame me. They took 14 computers from my house, all of my CDs, all of my DVDs, and I was away from the house at the time so I couldn't [ask] myself, "Do I have a porn DVD under the bed?" In the four months that followed I just had to cross my fingers and hope. I was frightened. And when there was no evidence found, it was all over.'

Except, of course, it may never be over. Despite his admission of misjudgment, and the fact that he was never charged, such associations are hard to shake off.

'I see it a bit like surviving cancer,' he says. 'Like a life-changing positive experience. God, the arrogance of me! I looked at myself and I thought, "Fucking hell, Pete, what did you think was going to happen?" And the fact that I had deliberately kept all my charity work secret ...'

He remembers when he first came across an image in 1998. 'I was researching to give money to an orphanage in Russia. I put these words in: Russian ... orphanages ... and then I thought "boys", so I put boys in, and this horrible porno picture came up of a child being buggered. The conceit of me! I was thinking, "I'm going to be the one to stop this ..." When I told Johnny Cusack, the actor, this story in the autumn of 2003, he said, "I think I know the picture you're talking about. Pete, it's Photoshop, it's not even real." I said, "Well, the damage is done. I saw myself. I saw myself." It probably never happened to me, but I saw myself and I saw millions of kids like me.

'I suppose it's true to say that it could have had a much worse effect had Roger not been so profoundly and powerfully behind me. My lawyers and I decided that I shouldn't speak. So Roger spoke for me, and he was such a powerful voice. I remember Bill Nighy saying to me, "Fucking hell, everyone could use a friend like that." Because the fact is that Roger didn't know what was going to happen.'

I wondered how his relationship with Daltrey had changed over the years.

'You know, it's survived. My marriage to my wife has not survived, and my marriage to Roger has survived, and it might be that only one of them could. I think you can only do one thing. I remember saying to [my wife] Karen, "I was a pop star when you met me," as though that would expiate the problem. The problem for her wasn't me going away [on tour]. She often used to say to me, "Goodbye, don't come back, just send a cheque ..." She just wanted me to be who she believed I was when I was home, and to be less affected by the ravages of the industry I was in. When I started to bring the ravages of my work home with me, it became harder and harder. She would go to me, "But it was great playing, was it?" And I would go, "No, it was fucking miserable." "But you're selling records, aren't you?" And I'd say, "Yeah, but it's a load of shit." And she'd say, "Well, why are you doing it then?" "Because I have to."'

Things have improved. He is still not divorced (complex property issues), but he is contemplating the matter again now that their third child is 16. He says that Rachel Fuller would like him to be divorced, and when I ask whether he plans to have children with her (she is considerably younger than him), he says they haven't talked about it. He adds: 'And as we don't have sex at all, it's not a problem.'

At the end of our interview, Townshend drives me to Richmond station in his small black Volkswagen Lupo. He also owns a Ferrari, but he gets a lot less hassle in the Lupo. On the way, he mentions the paucity of rehearsal time before the American tour, and the recent American anti-terrorism law that prohibits live webcasting. As he pulls up at the station he turns his face into the car, away from a pedestrian who has just begun to recognise him from his youth.

A week later, Roger Daltrey picks me up at Stonegate station in East Sussex in a new black Mercedes, and as he drives the short distance to his 400-acre estate he talks of how proud he is of Pete and the new album, and what a terrible time it is to be a farmer.

Wealthy rock musicians are traditionally assumed to inhabit baronial mansions, and Daltrey really does. 'It's 1610,' he says. 'It's coming up for its birthday.' He says that he bought the place 35 years ago for the magnificent view, but he's had a separate career just trying to maintain it. 'I lose money every year,' he says as he looks out onto his grazing cattle and freshwater fisheries. 'I have to go on bleeding tour just to pay for it.'

We settle in the lounge, while his second wife, Heather, and a grandchild amuse each other in the kitchen. The conversation drifts to the coverage of rock music on television ('The sound's got better, but the visuals have got fucking awful! All that swooping, whooping ...') and Live8 ('Absolutely appalling! All the things that Live8 was about in Africa, we did the same thing in Hyde Park - "them and us" with the Golden Circle [the privileged-access area at the front]. By the time we went on, the Golden Circle was exhausted, paralytic and asleep, and the real crowd at the back were going bananas').

At 62, Daltrey is stocky and exuberant. His golden locks have long been supplanted by a light brown crop. He says he is 'absolutely blind' without his blue-tinted granny glasses; he has considered laser treatment, but is frightened of error. He thinks he may have lost a few top notes over the years, but he is pleased how well his voice held up while recording the new material.

Not that he ever thought there would be new material. 'It's been a tortuous process,' he says. 'I thought, the idea was finished, this time last year. I thought, "Pete's got to let go of the Who." But the next thing I know Pete says, "I've done all the demos."'

Daltrey says he wrote six songs himself. 'None of them suitable, of course. I'll never be the songwriter Townshend is, I don't kid myself, but at least I came up with something. It's been a rough five years for us both, and how he's come through it, I don't fucking know.'

He told me he came through it because he had you and Rachel.

'I really love him. I do have to deal with the madness of some of his schemes. He's a technomaniac. I don't like the internet. I don't like the world he lives in. I don't think we've created a better society from the internet. Virtual relationships - I can't deal with that.'

I wondered whether the tension between the two of them - so evident and important onstage - was something they were keen to cultivate; not for the public image, but for their own creative wellbeing.

'Well, I feel very close to him,' Daltrey says. 'But we don't have to see each other all the time. It's a different closeness, and I really treasure it for that. The Who is the energy that exists between Pete and I, and that energy is increased by doing it separately. I don't care when people say we're not getting on - it's not fucking important. All that matters is what exists onstage and in our music. In that music is our relationship, is our love. I have such a deep love and respect for him, and that goes through all of it. He forgives all my foibles, and I forgive all his, and underneath all that I love him dearly.'

Daltrey says that it is getting a little harder every year to sing the old material, but it has never been easy. 'With the Who and Pete's music, you cannot cheat it,' he says. 'You cannot go through the fucking motions, because the music is just so gut-wrenching. It's so different from most of the other stuff that's out there, and you're got to be incredibly courageous to even attempt to do it.' He adds that there is still nothing that gives him greater artistic satisfaction than performing Townshend's songs. 'I don't get paid for the singing - that's free. It's the schlepping I get paid for.'

I had heard that the impact of John Entwistle's death four years ago was particularly sustained for Daltrey. 'I got very depressed,' he says. 'Very, very: it was much more of a shock to me than I ever thought it would be. I thought I had learnt to deal with those sorts of things, with mum, dad. John was John - you could never change him, a real rock'n'roll character and a real rock lifestyle. I mean does it matter, the sudden ending with the line of coke and the hooker in Las Vegas - I mean, is it that bad at 57? What's the alternative? The alternative may be very slow and smelly, as George Orwell said. All I know is that I fucking miss him.'

Daltrey had opted out of that hard rock lifestyle a long time ago. 'I wanted to sing. I had to decide very early on, especially when his writing got into the Tommy era - this stuff needs some interpretation and it needs an awful lot of discipline. You can't do the other stuff as well.'

And so Daltrey's other stuff has taken a different course - most notably towards charity and film work. I had asked Townshend why he had produced everything on the new album except Daltrey's vocals, and he said that Daltrey had a studio technique 'which is really quite eccentric. It's intense and extraordinarily self-obsessed.' But what really gets to Townshend is the thought, 'God, does Roger actually believe that all he does is sing?'

He also spends much time organising charity concerts for the Teenage Cancer Trust, a project he says has kept him sane following Entwistle's death. He is also trying to get a film made about Keith Moon, with Mike Myers playing the drummer. It's hard to get it exactly right, Daltrey says, because he doesn't want it to be Carry On Moon, the story that everyone knows. 'If I've done anything, I've stopped a bad Keith Moon film from being made.'

I ask him how he will know when the Who really is over. 'Oh, it will give me up,' he says. 'I just won't be able to sing it.'

But this may not be for a while. 'Can you see us onstage in wheelchairs?' he asks.

Not really.

'Why not? It will still be us, still be the same music, and it's only the music that matters.'

You'd have troubling swinging your microphone lead.

'Not necessarily. Pete may have trouble with the guitars, I suppose. He does like to jump around. I'm not saying I want to be in a wheelchair, but it could happen.'

It would certainly be a novelty.

'It would! I would never rule it out.'

Daltrey then took the photographer and his publicist and me on a little tour of his grounds in his Land Rover. We passed a woman who keeps the hawks that keep his rabbits down. We passed several fishermen by the edge of the beautiful lakes which he had made. At a fishing lodge, we paused to pick sweet plums from a tree. 'Just think,' one of us said to Daltrey, 'those lakes that you built are now going to be part of the English landscape for ever.'

'Nah,' Daltrey said. 'Nothing lasts for ever. Nothing. We're just pushing dust around.'

· Endless Wire is released on 31 October on Universal Republic

- The Observer 17/9/06

|

| 17th September 2006 02:38 PM |

|

|

| Ten Thousand Motels |

>Pete Townshend and Roger Daltrey are back and as vital as ever.<

Well, that's stretching it a little bit. |

|