|

|

| Ten Thousand Motels |

Pianist Bill Miller, 91; Framed Sinatra's Songs With Elegance

By Matt Schudel

Washington Post Staff Writer

Sunday, July 16, 2006; Page C07

Bill Miller, the pianist whose light touch set the mood for many of Frank Sinatra's most memorable songs, died July 11 at Montreal General Hospital at the age of 91. He had a heart attack after breaking his hip July 1 while on tour with Frank Sinatra Jr.

Mr. Miller was the elder Sinatra's elegant, steady and often inspired accompanist for nearly four decades and was one of the privileged few allowed into the singer's inner circle. For the past eight years, he had worked with Sinatra's son.

Mr. Miller, content to toil in the shadows for much of his career, provided the musical framework for some of the elder Sinatra's finest performances. He was best known for his pensive introduction to the torch song "One for My Baby," written by Harold Arlen and Johnny Mercer. Sinatra recorded the tune in 1958 and sang it in almost every concert until he stopped performing in 1995.

Mr. Miller's unhurried piano line sets the mournful tone for the heartsick ballad, with its haunting opening lyric: "It's quarter to three, there's no one in the place except you and me."

Both casual and responsive, Mr. Miller's piano part was the perfect foil for Sinatra's confessional storytelling in song.

"He plays undulating chords in the background with a peculiar mixture of empathy and detachment," Robert Cushman wrote in 1998 in the British newspaper the Independent. "He also offers a comment on the song and the man who sings it; he's the man who's heard it all before."

Mr. Miller said he originally improvised the introductory passage while playing the song in a nightclub. Sinatra liked what he heard and asked his arranger, Nelson Riddle, to build the rest of the musical score around the piano part.

"Once I figured out what I was going to do, we kept it that way," Mr. Miller told the Chicago Tribune in 1993. "Even now, when I play it, it's only with minor variations, because Frank is used to it a certain way, and it works. So why not leave it alone?"

Mr. Miller's piano was seldom featured as prominently in other tunes, but it helped shape the rhythmic backdrop for dozens of Sinatra's hits from the 1950s to the 1970s, including "Fly Me to the Moon," "You Make Me Feel So Young," "The Lady Is a Tramp," "It Was a Very Good Year" and "My Way."

"Bill's talent is quiet but always there," Sinatra once said.

In a story published last week in The Washington Post, Frank Sinatra Jr. said, "He's the greatest singer's pianist there ever was."

Mr. Miller was born Feb. 3, 1915, in Brooklyn, N.Y., and was 10 months older than Sinatra, whom he would later call "the old man."

By the late 1930s, he was part of two of the more advanced ensembles of the day, a small group led by vibraphonist Red Norvo and singer Mildred Bailey and a big band directed by Charlie Barnet. Mr. Miller also performed with bandleaders Tommy Dorsey and Benny Goodman.

He first met Sinatra in 1941, but they didn't join forces until November 1951, when they were both appearing in Las Vegas. The early years, when Sinatra was struggling with his voice and his turbulent marriage to Ava Gardner, were often difficult.

"If things went well, he was easy," Mr. Miller said. "If things weren't going well, it didn't matter whether he was right or wrong -- you were wrong."

Beginning in 1953, Sinatra made a series of recordings for Capitol Records that marked his artistic apex and remain classics of American music. Mr. Miller was the pianist on virtually every song.

Because Sinatra did not read music, he relied on Mr. Miller to convey his directions to conductors and other musicians. When the singer appeared with other groups, such as the Count Basie Orchestra, Mr. Miller often took over the piano chair.

An inveterate night owl, Mr. Miller had a pallid complexion that led Sinatra to introduce him onstage as Suntan Charlie. Over time their musical partnership deepened into genuine friendship.

"I was allowed to get closer to him than most people," Mr. Miller said. "After work, he liked to have a drink or two, and I like to have a drink or two, so we would hang out and talk about whatever was happening -- weather, current events, the things guys usually talk about."

But in 1978, after 27 years with Sinatra, Mr. Miller was abruptly dismissed.

"I'm not even sure about what caused the split," he said. "I was away for almost seven years. But then, all of a sudden, I found myself invited back to the piano."

Six months after Sinatra died in 1998, Frank Sinatra Jr. brought Mr. Miller out of retirement. He had to be helped to the piano from a wheelchair, but he remained musically and mentally alert to the end and performed on the younger Sinatra's new album.

"He was the greatest living authority on Frank Sinatra music," Sinatra Jr. told Variety magazine.

In November 1964, Mr. Miller's hillside home in Burbank, Calif., was destroyed in a mudslide. He was rescued from the hood of his car, but his wife, Aimee, was swept away and died. Sinatra identified her body at the morgue.

"Frank said, 'If it's any consolation, there wasn't a mark on her,' " Mr. Miller recently told The Post. "It wasn't any consolation."

He never remarried. His survivors include a daughter and a grandson.

[Edited by Ten Thousand Motels] |

|

|

| Ten Thousand Motels |

Frank Jr., the Unsung Sinatra

He's Got a Big Heart and His Pop's Voice, but Just A Shadow of His Success

By Wil Haygood

Washington Post Staff Writer

Sunday, July 9, 2006; N01

ATLANTIC CITY He loves the ghosts.

They can be standing, or sitting. They can be tucked away in vaults. Sometimes he'll just veer off a road, and there he stands, surrounded. Green trees and clear air.

"I went to visit my father's grave when I was in Rancho Mirage recently," Frank Sinatra Jr. is saying. "And as I was stepping away, I noticed the grave of Jimmy Van Heusen, who was buried a couple graves away from Frederick Loewe. I met Loewe once. Caesars Palace. Vegas. I was over there watching Sinatra do his show."

That's how he talks sometimes. As if the father were a whole other entity. Which is kind of sweet. And kind of tangled.

"Jimmy Van Heusen was a top security test pilot in World War II as well as being a great songwriter. He was absolutely incredible. Van Heusen inspired me to write music."

His band members refer to the father as Big Frank.

Junior is Frank.

And between those two singers, those two men, father and son, lies a mountain. One on one side because he's unreachable, the other on a lifetime climb because all he wants to do is sing, be respected, get another gig.

And the man throwing the shadow is always there.

Big Frank's crowd still calls him Frank's boy even if he's 62 now. The more he sings -- and legions will tell you he's hugely gifted in his own right -- the more it seems as if the ghost is tiptoeing from around the mountain, out of the shadows in his patent leather slip-ons -- right toward him.

Big Frank's been dead since 1998, yet still he's everywhere -- weddings, cocktail soirees, movie soundtracks, TV commercials, elevators. All Frank is trying to do is carve a niche into the rock of legend and fame and history.

Maybe in a more just world this Frank would have a bigger audience. His new CD, titled "That Face" -- his first studio album in a decade -- might have been released with more noise.

"There is no demand for Frank Sinatra Jr. records," Frank himself is saying.

"There never has been. Rod Stewart is now doing the Great American Songbook. So is Harry Connick Jr. and Michael Bubl?. Well, Frank Sinatra Jr. has been doing it for 44 years."

His voice is without an ounce of self-pity.

He hunches his shoulders. He turns, on a dime, away. As if the world has become just too damn difficult for anyone -- much less a Sinatra -- to decipher such things anymore.

On the Boardwalk

He is here in Atlantic City for a two-night gig at the Hilton on the Boardwalk.

He comes through the back door, 20 minutes early for rehearsal. He's carrying his own bag. He's in a gray shirt, black slacks, and black shoes that rise above the ankle. He gives off the aura of a very serious man.

He opens his briefcase and takes out his song list and lays it on a table. He pours himself a diet soda. Andrea Kauffman, his manager, hands him some black-and-white photos to autograph and some payroll checks to sign.

The orchestra then rolls into several numbers. Lovely and vibrant. Frank makes little marks with a black pen in his notebook.

"Terry," Frank says to a band member, "that clarinet line on the end is beautiful. So simple. Like Bartok."

His talking voice sounds just like Big Frank's on all those old TV specials when it was Frank and Dean and Sammy and everyone wore bow ties and tuxes with skinny lapels and the cigarette smoke was thick as fog and Big Frank's only boy was at college in California.

He's been with many of these musicians for decades. Some played with Big Frank.

Frank blows out his version -- ghostly, sweet -- of "On a Clear Day."

"That's Nelson Riddle," he says at song's end, "but he must have had on his Duke Ellington hat that day."

He muses aloud about the legendary conductor as if dreaming: "Nelson Riddle was really something. Just something else."

The sky outside has darkened, and it's raining cats and more cats. Some musicians look up at the roof, where the rain is beating.

They're into another number, "The People That You Never Get to Love." Halfway through, Frank motions for quiet from the 38-piece orchestra, then walks over and leans on the piano. "Let's try that again," he says. "It has to be half that volume, everybody. This is a lullaby. That's what it is."

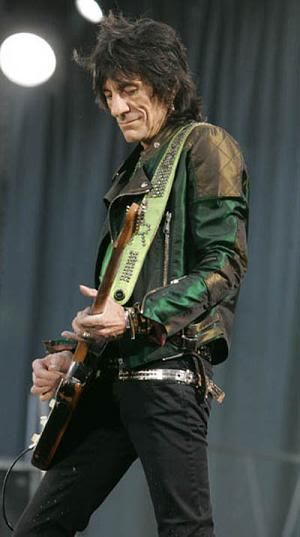

An old man - is helped from his wheelchair and led to the grand piano. Bill Miller, white-haired, beatnik glasses overpowering his face, leans over the keys.

"He's the greatest singer's pianist there ever was," Frank says, watching Miller as a father might watch his son walking across a log over a creek. Miller goes back decades with the Sinatra men. He played for Big Frank, served at one time as his musical director.

Miller never worried about the mountain or the shadows it cast. He's just the piano player.

"Take 10, everybody," Frank is soon saying.

Jim Fox, who looks like an aging surfer, sandy-haired and all, is Frank's guitarist. "He can sound exactly like his dad if he wants to," he says of Frank. "He can turn on the classic Sinatra sound anytime. It just depends on what kind of mood he's in. He has such high standards. He doesn't want to work unless he has his 38 band pieces. He knows every third trombone part, every cello part. You know, he conducted for his dad. So he knows the way Sinatra music is supposed to sound. He was at a lot of those original Capitol recording dates."

They live in an old world, this orchestra, a world of Ira Gershwin music and Johnny Mercer lyrics. Of Duke Ellington memories and Dinah Washington tributes.

"He's a great cat," Fox continues. "And he's really good to us. He takes us to dinner. Takes us to the best restaurants in town. He says it's the best thing for him -- to get us all out on the road, get us all together. Now, how sweet is that?"

After their break, Frank goes into "Come Rain or Come Shine." The ghost tugs at his memory. "You should have heard it the night it was recorded," he says of his father's version. "I shook."

Merrill Kelem sits in the auditorium. He was an Atlantic City police officer for three decades. Then he went to work security for Big Frank. "We didn't like using the word 'bodyguard,' " he says.

He works security for Frank now.

Kelem used to love being part of that squadron circling Big Frank. Leading Big Frank through the hallways, getting him to the limo.

Big Frank: There was the music -- years and years of it. But there were also headlines and scraps with newspapermen and marriages and divorces (Ava Gardner and Mia Farrow among them) and retirement and the legendary comeback. And more beautiful music for lonely, broken-hearted people. He was one Francis Albert Sinatra, and he knew how to wrap melancholy around a lyric, and he was a decent actor, and he had some tough and shady friends, and he was a great pal to his allies, and he even paid their hospital bills when they couldn't, and he gave hugely to charities, and he said Billie Holiday was one of his great influences. And when his shows opened and the musicians started wailing, you couldn't see him just yet. And then he'd rise from the half-hidden milk crate he had been sitting on with his back to the audience, without any formal introduction, and he'd turn to the audience and watch them go wild. And he had children: two daughters, and one son, Frank Jr., by his first wife, Nancy. And therein lies the history, and the shadowing, and the blue-lit ghost against the mountain.

The great Bill Miller, who had played all those years with him, went home after Big Frank died. There wasn't much work. Mostly, he was alone. Who knows what an old pianist sitting alone thinks about? The phone rang. It was Frank. Let's go, he said.

'He Was Good to Me'

The pianist was born in 1915. He's slim and the body is bent. The bent body looks almost courageous, as if he's been pummeling things mortals can't see. His fingers are long and pink and elegant. He likes a little vodka in the evenings. He likes Key lime pie. He's never done his own album. "It never came about," he says. "It's a little late now. But" -- and he lifts a hand like a bird's wing rising slowly up from a nest -- "who knows?"

His piano on the potent Sinatra number "One for My Baby (and One More for the Road)" is considered classic. "That was an accident, really," Miller says. "We did the recording after two or three takes. You just hope for the best. I got lucky with that."

During a time of great romantic ballads, Bill Miller found love with a woman by the name of Aimee. They married, and sometimes she would join him on the road. Her love, his piano: Life was sweet. In 1964, they were living in California with their small daughter when a rain-soaked mountainside gave way, unleashing a torrent of mud and water. The family was separated. Miller's daughter somehow made it safely to the top of a hill. Bill was washed away in the debris, found clinging to a car at the end of a road.

They found Aimee the second night. Bill looked up from his hospital bed to see Big Frank standing over him. "Frank identified her body," he says. "Frank said, 'If it's any consolation, there wasn't a mark on her.' It wasn't any consolation."

Big Frank replaced everything for Bill. "The old man, he was good to me," Miller says.

'A Singer by Accident'

It's dinnertime. And there's a long table at this upscale steakhouse. And Frank's got most of the orchestra around him.

He's actually kind of shy.

Armchair music analysts wonder about his psyche, how he has coped -- with the image, the legend, the name. The rocks that built the mountain over the years.

"When I started as a kid, I wanted to be a piano player and songwriter. I only became a singer by accident," he says. "I was in college, playing in a little band. The lead singer got tanked one night. A guy in the band pointed at me and said, 'You sing.' I said, 'Me? Why me?' He said, 'You're a Sinatra, aren't you? Sing!' "

He really never saw much of his father in those days. "He was unreachable. He was traveling, or off making some movie. When I began in this business, it was only on rare occasions when we saw each other."

So he went on the road himself. Older musicians talked to him about life, love, women, their world.

"A lotta years I was out there on the road pulling one-nighters. Then I got hired to sing in Sam Donahue's band in 1963. I was 19 years old. Those days were so much more easier to work than it is today. There was no such thing as a $4 can of gasoline. And there were places to work. Now it's only rock music. Ask somebody who Gershwin is, who W.C. Handy is, they wouldn't have the slightest notion. I'm talking people up to 30."

He orders a charred ribeye.

"I was never a success," he says. "Never had a hit movie or hit TV show or hit record. I just had visions of doing the best quality of music. Now there is a place for me because Frank Sinatra is dead. They want me to play the music. If it wasn't for that, I wouldn't be noticed. The only satisfaction is that I do what I do well. That's the only lawful satisfaction. I was never a rock singer. I lost my job at RCA Victor in the '60s because I wouldn't sing protest songs like all those other groups were doing at the time."

Band members talk of his generosity. Not long ago, Frank bought every band member a fancy oxygen mask: He'd been caught in a hotel fire once. They talk of missed gigs and the check still arriving in the mail.

"In this town they used to have a place called the Steel Pier," Frank is saying. "At the Steel Pier, I used to alternate with a young boy I had never seen before. He was cleanshaven. It was Stevie Wonder. We used to alternate onstage with Duke Ellington. Duke took me under his wing. And I listened to the sounds he made."

He moved through the years, away from his father, Big Frank, and into his father and around his father, and into his father yet again.

He studies wartime bands with the intensity of a scholar. "The real powerful band era didn't come till after the war was over, around 1948. Then came the era of the vocalist. There was the Eddie Sauter and Bill Finegan Orchestra. The late '40s. They had a jazz band. They luxuriated in the French harp. A little bit of the symphonic touch. It was quite something to hear. Them and Stan Kenton's band. They made bands reach heights they had never reached before. More for listening than for dancing. That was the period I was interested in."

He's hardly touched his steak. He asks if everyone is happy with the food.

"When I started out I worked with Ziggy Elman, Charles Shavers, Louis Armstrong. I sang with Harry James's band -- with Harry. I sang with Woody Herman's band -- with Woody."

He'd like the world to know he was never a dilettante. That he works like a demon.

Once, on the road, he found himself in D.C. He had a gig someplace in town and afterward got himself over to Charlie's, a club. "I went over to Charlie's to listen to Al Hirt. In the bathroom there was this old man -- he ran the bathroom -- who gives me a towel. I look above the mirror and notice there's a picture of Sy Oliver's band. I said, 'What are you doing with a picture of Oliver's band?' He said, 'Boy, how you know that band?' I said, 'You play?' He pointed to the picture and said, 'That's Louis Armstrong. And that's me, second clarinet.' I went back outside. I said to Al, 'Al, there's a guy in the bathroom who played in Sy Oliver's band.' Al went and got him and pulled him up onstage. He must have been 85 years old. He still had his chops."

Frank Sinatra Jr. is single. He was married once but it didn't work out. He remains close to his two stepdaughters. He has a son, Mike, from another union. Mike attends the University of California at Santa Barbara. He doesn't sing. "Thank heavens," Frank says.

He wishes he himself could get more work. "The exhibitors see a show with 38 musicians, stage crew, and they get sticker shock. The show is expensive to put on."

This year, for the first time in five years, they've got a New Year's Eve gig. You wonder: Manhattan, maybe, Vegas?

They'll be going to Spokane.

He's grateful, though. "We used to work every New Year's Eve," he says. "Now they give people champagne, karaoke and confetti -- and the people are delighted."

It saddens him.

"Sinatra had this magnificent talent of picking the right stuff for him," he says about his father's endurance. "In those days, of course, there were a lot of songwriters to pick from. Today, whose left? Leslie Briscusse, Neil Sedaka, Rupert Holmes. Most of it has long since passed. But it's okay. You can always reach into the past."

The dinner bill for the orchestra arrives.

Frank pulls out a wad of cash. He came from that money-talks world. He leaves a heap of it on the table, including a generous tip. And he's gone.

Bill Miller, however, is not ready for bed. He sits stabbing a fork into a slice of Key lime pie. Johnny Pizza sits near him, full and happy. Frank hired Pizza mostly to help out Miller. Pizza wears an impressive diamond ring -- black center, diamonds circling the outer ring.

"When do we open?" Bill asks Johnny.

"Tomorrow, Bill," Johnny says.

"Tomorrow? Fair enough," Bill Miller says.

'Strangers in the Night'

They come from Cherry Hill and Philadelphia, from Manhattan and Newark and Trenton. "New Jersey is Sinatra country," Frank had said at dinner. "We always get a good reception here."

They come for him, and for his father. (Some come because of more recent intrigues: That was Frank a few years back appearing on an episode of "The Sopranos." Frank played a card sharp. He got a kick out of it.)

They come muscled and they come fragile, leaning on canes. The line at the Atlantic City Hilton starts forming two hours before show time.

They fill the house, 1,450 seats.

Eddie Stasny, 77, wouldn't miss it for the world. He arrives early from Cherry Hill. He's president of something called the Sinatra Social Society. Eddie's in a blue suit with a red hankie. Big Frank knew him personally. "I miss him terribly," he says. "I was his guest at Carnegie Hall, 1979, when the 'Trilogy' album came out. We were in the dressing room with him before the show."

Eddie has great admiration -- and some sympathy -- for the son, for Frank. "It's not easy to follow a giant like that," he says.

"I like the new album," he says about Frank's new release. "It came out on the 6th. I went to Tower Records the next day. The clerk didn't know nothing about it. They had five copies."

The Sinatra society he heads used to have upward of 200 people. "I got about 125 people left," he says. "We used to go everywhere. But it's dwindling down. The age factor. And a lot of people can't drive at night. I do okay myself."

It's 20 minutes till show time. Eddie pops up like a cork from his seat. Gotta get backstage -- again. Just remembered something else he's gotta tell Frank.

Rose Marcie used to go see Big Frank regularly in the '70s. "Junior does his own show, and he's wonderful," says Rose, who's come in from Philly wearing an eggshell white outfit. She goes on: "Close your eyes and give Junior his credit. I do it all the time. I look away -- to make sure I'm not looking at him to make it be his father."

The lights dim. There's no warm-up act, just an instrumental version of "Witchcraft."

Then Frank -- no announcement -- just saunters out onstage. As if he were trying to slip off someplace and got caught. They start clapping, and he stops cold. Grins, then mouths a "Who me?"

He opens with a song called "Lonesome Road."

He holds the mike like a martini glass.

"This is our first gig at the Hilton in five years," he says, pulling a stool close. "You can see they were dying to have us back."

He knows how to deliver a funny line. He used to work alongside the vaudevillian George Burns.

They do "Strangers in the Night" and "Summer Wind." They do "Luck Be a Lady," and Frank pantomimes throwing a pair of dice into the audience.

Rose looks away. Eddie Stasny pokes his wife.

Frank disappears backstage, and his voice, that Sinatra, calls into the velvet darkness from somewhere back in '52: "This man's music will be heard for centuries to come, ladies and gentlemen."

He introduces Bill Miller. A spear of light cuts the darkness and falls onto the old man at the piano and Frank, now standing near him. They slide into "One for the Road" like Ava Gardner slipping into mink.

He goes into "New York, New York": "C'mon," Frank says over the wild applause. "You know I had to do this one."

He takes them in and out of his world, and Big Frank's world. "That man," he says, "played this town for decades."

Afterward, the audience rises up. Some -- rush wouldn't be the right word, but they get there quick enough -- make their way to the stage.

"Let me by!" Eddie Stasny says to anyone in his way.

"He came to my high school in Trenton back in the '60s," a beefy man calls out, making his way toward Frank.

Frank accepts handshakes and congratulations. He cradles a bouquet of flowers.

Backstage, there are more hugs. Frank is smiling. He wipes beads of sweat from his brow with a handkerchief. He seems happy, not least with the height of the mountain. Miller sits a few feet away, behind a slip of velvet curtain.

"I'll see them all," Frank says about the folk lined up.

Miller listens to the hubbub. He's been hearing it for decades.

The old pianist never remarried. He met his Aimee back in 1942. Here, in Atlantic City. In a bar.

Bill Miller sips the last of his drink.

And one more for the road . . .

Then he and Frank leave through the blue smoke of all the ghosts. Headed to Canada for a gig.

|

|

|

| Ten Thousand Motels |

Bill Miller

February 3, 1915 - July 11, 2006

Rest In Peace

-----------------------------------------------------------

Frank Sinatra lyrics

One for my baby (from duets)

Writer(s): johnny mercer/harold arlen

Its quarter to three,

Theres no one in the place cept you and me

So set em up joe

I got a little story I think you oughtta know

Were drinking my friend

To the end of a brief episode

So make it one for my baby

And one more for the road

I know the routine

Put another nickel in that there machine

Im feeling so bad

Wont you make the music easy and sad

I could tell you a lot

But you gotta to be true to your code

So make it one for my baby

And one more for the road

Youd never know it

But buddy Im a kind of poet

And Ive got a lot of things I wanna say

And if Im gloomy, please listen to me

Till its all, all talked away

Well, thats how it goes

And joe I know youre gettin anxious to close

So thanks for the cheer

I hope you didnt mind

My bending your ear

But this torch that I found

Its gotta be drowned

Or it soon might explode

So make it one for my baby

And one more for the road

[Edited by Ten Thousand Motels] |

|