|

|

| Mel Belli |

Anthony Lane, lukewarm:

http://www.newyorker.com/arts/critics/cinema/2008/04/14/080414crci_cinema_lane

THE CURRENT CINEMA

NOT FADE AWAY

“Shine a Light.”

by Anthony Lane

APRIL 14, 2008

Martin Scorsese films the Rolling Stones live over two nights in New York.

n the seventeenth chapter of “The Voyage of the Beagle,” Charles Darwin turned to the mating habits of the giant Galápagos tortoise. “When the male and female are together, the male utters a hoarse roar or bellowing, which, it is said, can be heard at the distance of more than 100 yards,” he wrote. This is also the most accurate description that we possess of the duet performed by Mick Jagger and Christina Aguilera in “Shine a Light,” Martin Scorsese’s documentary on the Rolling Stones. All four members of the band are now in their sixties, and the film offers a few wry nods to the passage of time; there is, for instance, an old clip of the young Jagger, Byron-beauteous, saying that the band plans on staying together for another year, at least. And just look at him now: talk about the survival of the fittest. As for Keith Richards, he’s more like a tortoise than ever, unworldly-wise, dipping his graven face to browse fondly over his strings.

The film records a pair of concerts that the band delivered, over two nights, at the Beacon Theatre in New York in 2006. For the first twenty minutes, we follow the anxious buildup, with shots of Scorsese asking, in kindly exasperation, whether he might possibly have a sneak preview of the playlist for the night. Someone finally hands him a crumpled copy, with about nine seconds to spare. The sight of a director making preparations for the movie we are currently watching could easily give off a whiff of self-indulgence, yet these scenes come across as the most interesting of all, with their hint of a clash between the neat, persnickety approach of the filmmaker and the time-weathered whimsy of the act that he is striving to capture, not to mention the restricted shooting space around the stage. “It would be great to have a camera that moves,” a plaintive Scorsese says, which is like Rembrandt asking if he could have a little bit of brown.

On the other hand, these pre-concert sequences hold out a promise that the film refuses to keep. We see Bill and Hillary Clinton, who were present with friends and family for one of the shows, rolling up beforehand to meet and greet: an effusive occasion, as Hillary’s mother is enfolded by Keith Richards with a gusto that you or I would reserve for a warmly remembered lover. (“Hey, Clinton, I’m bushed,” he says to the camera, giggling like an eight-year-old.) The former President, who is hosting the performance as a benefit for his foundation, recalls a previous Stones event, when the cause was climate change. The Stones, he says, “know as much about this stuff as we do.” This would surely be news to Keith, for whom climate change is what happens when you open the fridge door. But once the music is under way the Clintons vanish from sight; we are constantly shown the kempt young women who line the outthrust runway at the front of the stage, the better to gaze crotchward at the advancing Mick, but there is not a single shot of the Clintons in mid-gig, shaking their respective booties, and thus we will never know what expression Hillary chose to wear when Jagger invited Buddy Guy to join him in a rendition of the old Muddy Waters number “Champagne and Reefer.”

That song, one of eighteen played live in the film, is an undoubted highlight, not only because the performers give every sign of having confirmed the lyrics with extensive background research but because, when Guy plays guitar, he holds still. What a relief. For most of the time, “Shine a Light” is a fizzing and frantic work—all champagne and no reefer, you might say—and one longs for the merest whisper of a lull. Scorsese employed a small army of first-rank cinematographers, headed by Robert Richardson, and including Robert Elswit, fresh from his Oscar success for “There Will Be Blood,” and Andrew Lesnie, the director of photography on the “Lord of the Rings” trilogy, and thus tailor-made for the Stones, who in their tireless devotion to fellowship and pleasure have come to resemble elongated hobbits. As usual, the most phlegmatic is Charlie Watts, dandyish and self-contained, puffing his cheeks for the camera at the end of a song, as if to indicate, “Well, thank God that’s over.” It is a rare hint, in a movie giddy with self-persuasion, of someone not too elderly but simply too grown up to play the game.

There is a niggle here, as we skim from Stone to Stone. To equip yourself with multiple cameras might seem like hiring a batch of instrumentalists for a rock group or a chamber orchestra, but musically you can mesh and layer your sounds together, whereas all that Scorsese can do—what he may have felt obliged to do, with so much talent under his command—is chop and change. At a guess, I would say that the average length of a shot in “Shine a Light” is around four seconds, with Scorsese and his editor, David Tedeschi, flipping between the cameramen as they grab a slice of closeup. One of them manages to focus on Keith, in the depths of a song, as he discards a cigarette not by stubbing it out, like a regular mortal, but by spitting it out, in a spray of bright sparks. Whoever caught this, it’s a gorgeous, one-in-a-million shot. Still, I was left wondering: the closeup is, by definition, the most in-your-face approach to the impact of rock, but does it honestly suit the Stones, and, in particular, the singular figure of their front man, writhing like an electric eel in black pants? Thanks to the camera angles of “Shine a Light,” I can tell you exactly how many fillings Jagger has on the upper right side of his back teeth, but not until we see him in full length does he cohere and convince. Only then do we understand his gender-crunching brio—the rutting, ballsy yowl of the voice paired with that oddly feminine hip twist and shimmer of the shoes. It takes nerve, being an alley cat on the catwalk.

My unease, under the glare of “Shine a Light,” had nothing to do with my lifelong indifference to the Rolling Stones. I was no great fan of Talking Heads, either, until I saw “Stop Making Sense,” Jonathan Demme’s concert picture of 1984, which felt altogether calmer and less pummelling than Scorsese’s effort. The hipness of its wit suffused both design and mood, and when David Byrne delivered “Once in a Lifetime” Demme framed him from halfway up and did him the honor of keeping our gaze steady throughout, trusting not in any fancy moves but in the near-desperate surge of the song itself. That same trust was there in “The Last Waltz” (1978), Scorsese’s wistful record of The Band as they bowed out of existence, with the ramshackle aid of Bob Dylan, Joni Mitchell, and other deities, but it has gone missing from “Shine a Light,” and its absence provokes a nagging question: Can you, or should you, forge a movie from a cluster of hot images, and nothing else? I watched this film at an IMAX cinema, and, believe me, there are better things for a throbbing head than a fifty-foot-high enlargement of Ronnie Wood. At times, the cutting shifts from the hasty to the impatient to the borderline epileptic, and, while never doubting Scorsese’s ardor for the Stones, I got the distinct impression of a style in search of a subject.

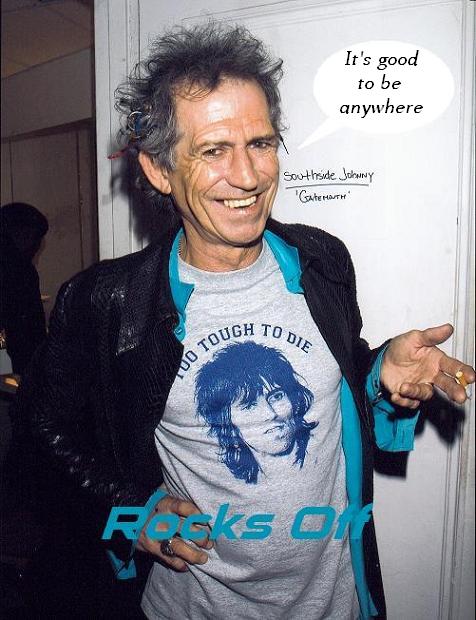

The same thing happened with “The Aviator” and “The Departed,” films that felt driven by their own fluency and facility but by no more pressing desires. What Scorsese adores in the Italian cinema that flared up at the end of the Second World War and burned through the next twenty years, and what he himself sought to rekindle in his early New York movies and in “Raging Bull” (1980), was a sense of tales crying out to be told, and of directors being forced into new and incendiary ways of telling. I would trade the whole of “Shine a Light” for the pre-credit sequence in “Mean Streets” (1973), when Harvey Keitel’s head hits the pillow and the Ronettes burst and clatter onto the soundtrack with “Be My Baby.” At that moment, it is true, we get three fast cuts of Keitel’s night-darkened face, but they come after a long, uninterrupted forty-second take of his wanderings around the bedroom, and so the sudden visual quickening matches the thrill of the sound; we seem to hear a beat in Keitel’s head, like a pulse in his temple, and it answers to the rhythms of need and jumpiness that will power the rest of the movie. And that, in turn, shows us the hole at the heart of “Shine a Light”: it is a film without a need. You could argue that the Stones feel a bizarre compulsion to carry on touring, for fear, perhaps, of how their lives would stall without these invigorating jolts; but that is their problem, not Scorsese’s, and the worst thing that could happen is that he might wind up like Mick, Charlie, Ronnie, and Keith—doing his stuff just because he can. “It’s good to see you again,” Richards says to the throng, adding, “It’s good to see anybody.” The line gets a laugh, but I hope it sounds a melancholy warning note to Martin Scorsese. At sixty-five, he has so much more to impart than that, in his grapplings with the world, and maybe for his next project he should head back to the mean streets of his youth and do what the Rolling Stones have never dared to do and, on the evidence of “Shine a Light,” never will: make art out of growing old. ♦

|

|

|

| gimmekeef |

The guy longs for the mere whisper of a lull?...WTF was he doing at a Stones show then? Go back to reviewing the fucking opera. |

|

|

| Steel Wheels |

He's a fucking Talking Heads fan.

Next! |

|

|

| Ten Thousand Motels |

>My unease, under the glare of “Shine a Light,” had nothing to do with my lifelong indifference to the Rolling Stones.<

Whew, ....

|

|

|

| Mel Belli |

At first I disagreed with the thrust of the review, but thought it was well-written. But when you isolate quotes from it like that it, I realized how pompous it is. |

|

|

| texile |

the new yorker, the village voice and that ilk -

ALWAYS pompous and smug and worst of all, aloof.

i haven't seen shine a light but there was a similar 'review' in the houston chronicle last week -

the guy admitted he knew nothing and cared nothing about the stones....

i get that - the best reveiws are those that use a critical and disconnected eye toward the subject, but complete ignorance is just laziness. a negative review from someone who understands the stones place in cultural history is one thing (i usually love those - and usually agree) but a lack of cultural awareness is just empty.

the stones cannot be fathomed without real research into their catalogue and history....

what else can we expect from these kinds of reviews.

|

|

|

| glencar |

This guy is pompous. It sounds like his biggest disappointment is that we never saw the Clintons again after the opening segment. A real douchebag. |

|